In the agricultural heartland of the state, restored floodplains are battling both drought and flooding. However, the influential farmers in California control their destiny.

This story originally appeared on Grist. It was produced by Grist and co-published with Fresnoland. It is part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Central Valley’s land is hardworking. In the most fruitful farming region in the US, right here in the heart of California, practically every square inch of land has been cleared, planted, and sculpted to accommodate large-scale agriculture. Nuts, walnuts, pistachios, olives, cherries, beans, eggs, milk, beef, melons, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, and garlic are all produced in the valley.

Even at a glance, this economic obligation is evident: Tractors carrying loads of fertilizer or diesel drive along arrow-straight highways, passing square field after square field, all densely planted with nut trees or tomato shrubs. Slicing through acres of silage and orchards, canals transport vital irrigation water from farm to farm via a system of laterals. In densely populated dirt patches, cows compete for space under metal awnings, sending a foul smell throughout neighboring towns.

There is one exception to this law of productivity. In the midst of the valley, at the confluence of two rivers that have been dammed and diverted almost to the point of disappearance, there is a wilderness. The ground is covered in water that seeps slowly across what used to be walnut orchards, the surface buzzing with mosquitoes and songbirds. Trees climb over each other above thick knots of reedy grass, consuming what used to be levees and culverts. Beavers, quail, and deer, which haven’t been seen in the area in decades, tiptoe through swampy ponds early in the morning, while migratory birds alight overnight on knolls before flying south.

According to Austin Stevenot, who oversees the upkeep of this regenerated jungle of water and untamed flora, this is the intended appearance of the Central Valley. Yes, this was the original appearance of the country for countless years until European settlers changed it to accommodate large-scale industrial agriculture in the 19th century. Stevenot’s California Miwok tribal ancestors used the local plants for cooking, weaving baskets, and manufacturing herbal remedies in the days before colonialism. Those plants have now come back.

As we drove through the flooded terrain in his pickup truck, he said to me, “I could walk around this landscape and go, ‘I can use that, I can use this to do that, I can eat that, I can eat that, I can do this with that.” “I view the ground differently than you do.”

You wouldn’t know it without Stevenot there to point out the signs, but this untamed floodplain used to be a workhorse parcel, just like the land around it. The fertile site at the confluence of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne rivers once hosted a dairy operation and a cluster of crop fields owned by one of the county’s most prominent farmers. Around a decade ago, a conservation nonprofit worked out a deal to buy the 2,100-acre tract from the farmer, rip up the fields, and restore the ancient vegetation that once existed there. The conservationists’ goal with this $40 million project was not just to restore a natural habitat, but also to pilot a solution to the massive water management crisis that has bedeviled California and the West for decades.

The Central Valley, like many other regions of the West, is perpetually plagued by either an excess of water or a shortage of it. Farmers extract groundwater from aquifers during dry years, when mountain reservoirs dry up and the surrounding land begins to sink. When the reservoirs overflow in rainy years, water pours down rivers and breaches deteriorating levees, submerging farms and valley villages.

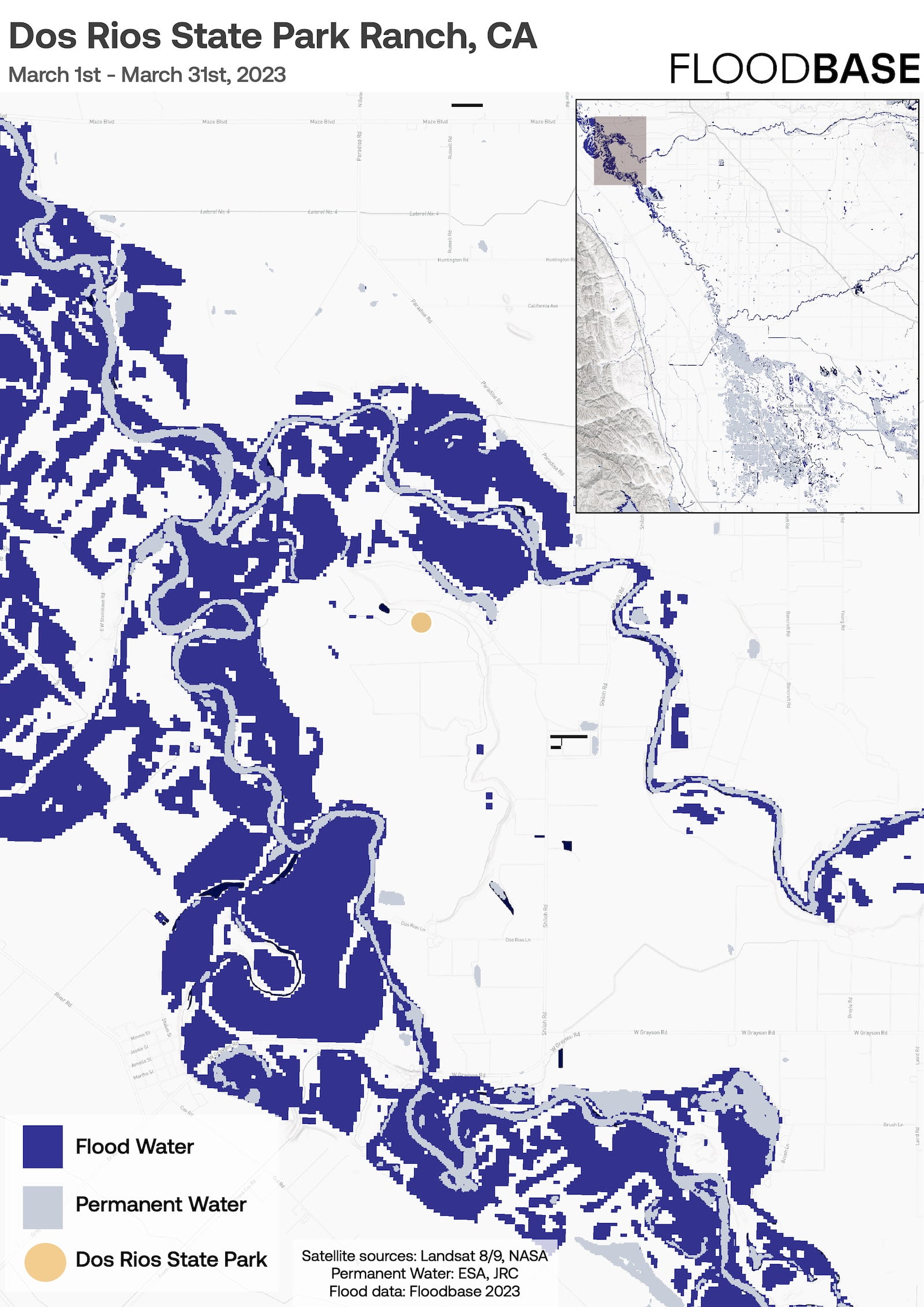

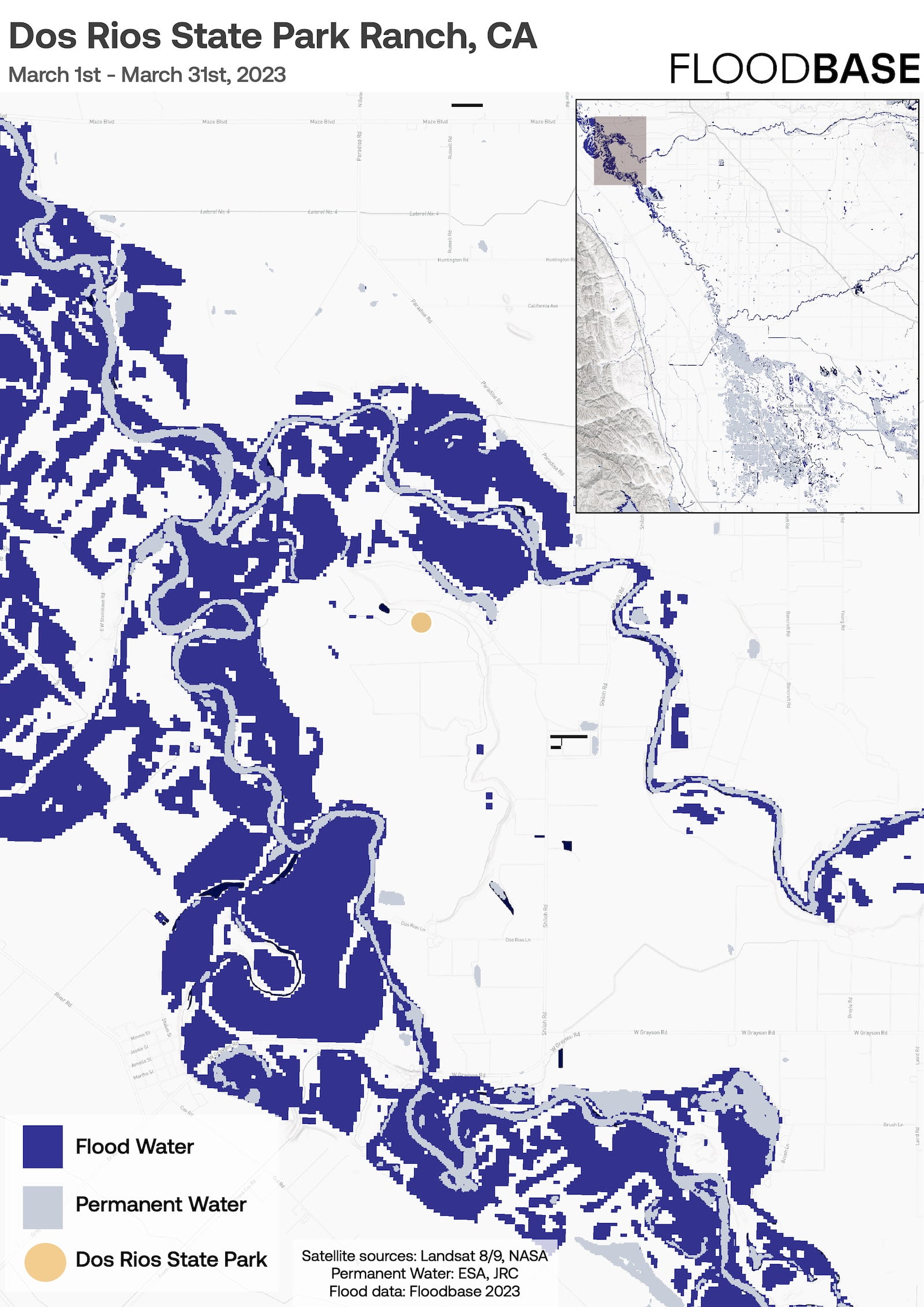

The restored floodplain solves both problems at once. During wet years like this one, it absorbs excess water from the San Joaquin River, slowing down the waterway before it can rush downstream toward large cities like Stockton. As the water moves through the site, it seeps into the ground, recharging groundwater aquifers that farmers and dairy owners have drained over the past century. In addition to these two functions, the restored swamp also sequesters an amount of carbon dioxide equivalent to that produced by thousands of gas-powered vehicles. It also provides a haven for migratory birds and other species that have faced the threat of extinction.

“Watching nature reclaim it has been incredible,” Stevenot remarked. “A commercially farmed orchard or field is sterile if you just stand there and listen to it.” You hear nothing at all. However, when you arrive here that day, you hear birdsong and insects. It is the beginning of the lowest portion of the ecosystem.

Stevenot’s professional journey is a reflection of the land he currently farms. Prior to joining River Partners, the small conservation group that created the website, he worked for eight years at a packing house that prepared onions and cherries for national export. Despite having lived in the San Joaquin Valley his entire life, he had never had the opportunity to put the customs he had learned from his Miwok family to practice until he began performing routine maintenance at the floodplain project. He now rules the entire environment.

This year, following an abundance of snow and winter rain, water from the Tuolumne and San Joaquin rivers flooded the site, causing it to full up for the first time since it was restored. Stevenot showed me all the ways that land and water interacted as he led me through the landscape. In one place, the distinctions that had once separated the property’s acres had been erased by water spreading like a sheet across three former fields. Where there had previously been an ordered orchard, birds had distributed seeds, and soon the original furrows were hidden by new trees.

This little portion of the San Joaquin Valley has greatly benefited from the start of the restoration project known as Dos Rios, which has ended the region’s recurrent floods and changed long-held beliefs about environmental preservation. Nevertheless, it’s still only a crack in the Central Valley’s armor, where agricultural interests still hold nearly total control over the land and water. Replicating this effort is more important than ever, according to flood experts, as climate change intensifies California’s weather whiplash, causing a cycle of drought and flooding.

However, acquiring the funds to purchase and reforest thousands of acres of land is only one aspect of creating another Dos Rios. Reaching an agreement with a big industry that has historically clashed with environmentalists—and that supplies fruit and nuts to a large portion of the nation—is also necessary to construct a network of restored floodplains. In order to fulfill Dos Rios’ pledge, farmers in the state will need to be persuaded to use less water for irrigation, occupy less land, and produce less food.

Such a change is feasible, but difficult, according to Cannon Michael, a sixth-generation farmer who oversees Bowles Farming Company in the center of the San Joaquin Valley.

“A lot of people are aging out and not always returning to the farm, there’s a limited resource, a warming climate, a lot of constraints,” Michael stated. In any case, a lot of transition is occurring, and I believe that people are beginning to realize that things in life will change. And I believe that those of us who wish to remain in the valley will try to find a way to live with the result.

Consider the past hundred years of Central Valley environmental management as a continuous endeavor to establish stability. Farmers who want to grow these products cannot simply depend on water falling from the sky since alfalfa fields and citrus orchards require copious amounts of water, and nut trees require years of constant watering to reach maturity.

In the early 19th century, as white settlers first claimed land in the Central Valley, they found a turbulent ecosystem. The valley functioned as a drain for the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, sluicing trillions of gallons of water out to the ocean every spring. During the worst flood years, the valley would turn into what one 19th-century observer called an “inland sea.” It took a while, but the federal government and the powerful farmers who took over the valley got this water under control. They built dozens of dams in the Sierra Nevada, allowing them to store melting snow until they wanted to use it for irrigation, as well as hundreds of miles of levees that stopped rivers from flooding.

However, the government and the farmers also dried out a large portion of the valley’s soil by limiting the rivers’ flow, depriving it of the floodwaters that had supported it for ages.

Historically, floodwater would disperse throughout nearby areas along riverbanks and remain there for several weeks, according to Helen Dahlke, a hydrologist at the University of California, Davis who specializes in managing floodplains. That is how we renew our groundwater reserves and what fed the sediment. The issue is that the land is currently mostly utilized for other reasons, even though the floodwater absolutely has to be on land.

Families like Bill Lyons’, the rancher who had owned the area that became Dos Rios, were able to profit as a result of the valley’s growth. As the third generation’s successor to a farming dynasty that started when his great-uncle E. T. Mape immigrated from Ireland, Lyons is a family farmer. Lyons, who formerly held the position of secretary of agriculture for the state of California, epitomizes the modern California farmer with his shock of gray hair and his go-to outfit of starched dress shirt and jeans.

Over the past few decades, Lyons has extended his family’s farming business, extending his dairy farms and nut orchards over thousands of acres on the west side of the valley. However, his domain crosses the San Joaquin River, and in the rainy seasons, one farm property consistently appeared to be submerged.

Lyons stated, “One of the things that drew us in was the ranch’s extraordinary productivity.” Although the terrain was fertile due to its low-elevation river frontage, the same geology also put the harvests at risk of floods. “I think we were flooded out two or three times in the 20 years that we owned it,” Lyons continued.

In 2006, as he was repairing the farm after a flood, Lyons met a biologist named Julie Rentner, who had just joined River Partners. The conservation nonprofit’s mission was to restore natural ecosystems in river valleys across California, and it had completed a few humble projects over the previous decade, most of them on small chunks of not-too-valuable land in the north of the state. As Rentner examined the overdeveloped land of the San Joaquin Valley, she came to the conclusion that it was ready for a much larger restoration project than River Partners had ever attempted. And she thought Lyons’ land was the perfect place to start.

Most farmers would have bristled at such a proposition, especially those with deep roots in a region that depends on agriculture. But unlike many of his peers, Lyons already had some experience with conservation work: He had partnered with the US Forest Service in the 1990s on a project that set aside some land for the Aleutian goose, an endangered species that just so happened to love roosting on his property. As Lyons started talking with Rentner, he found her practical and detail-oriented. Within a year, he and his family had made a handshake deal to sell her the flood-prone land. If she could find the money to buy the land and turn it into a floodplain, it was hers.

Rentner found the process to be anything but simple. She had to scrounge up $26 million from three federal agencies, three state agencies, a local utility commission, a nonprofit foundation, the electric utility Pacific Gas & Electric, and the beer company New Belgium Brewing in order to buy the land from Lyons and the $14 million more she needed to restore it.

Rentner recalled taking numerous excursions there, during which her colleagues in public financing agencies would ask her, “Now that you have a million dollars, how many more do you need? In what manner will you arrive there?

In response, Rentner said, “I don’t know.” “I guess we’re just going to keep writing proposals.”

Even after River Partners purchased the land in 2012, Rentner was faced with a never-ending maze of permits: every grant had specific guidelines for what River Partners could and could not do with the funds, the deed to Lyons’ tract had limitations of its own, and the government mandated multiple environmental reviews to guarantee the project wouldn’t negatively impact sensitive species or adjacent land. In addition, River Partners had to host numerous community gatherings and listening sessions to allay the doubts and anxieties of the farmers and neighbors who were concerned about intentionally flooding a farm by closing it down.

Now that the project is finished, it is evident that all of those worries were unwarranted, even though it took River Partners more than ten years to accomplish. The massive “atmospheric river” storms that pounded California this winter left the repaired floodplain saturated, holding all the extra water without inundating any private land. There are no job losses in the surrounding towns as a result of the removal of a few thousand acres of agriculture, and local government finances are unaffected. In fact, the project’s groundwater recharge could soon contribute to the rehabilitation of the hazardous aquifers beneath neighboring Grayson, where a population of around 1,300 Latino agricultural laborers has long shunned nitrate-contaminated well water.

The floodplain is developing into a self-sustaining ecosystem as new plants take root; with a complete hierarchy of pollinators, base flora, and predators like bobcats, it will endure and regenerate even during future droughts. River Partners doesn’t need to do anything to maintain Stevenot indefinitely, except from regular cleanup and road repairs. The state will take over the land the following year, and visitors will be able to explore new paths while it remains open as California’s first newly created state park in almost ten years.

“We walk away after three years of intensive cultivation,” Rentner remarked. “We ceased performing any restoration work at all. As we’ve seen, the plant learns to survive on its own and is tough. When there is a large, deep flood, like the one we had this year, the natural materials reappear.

Dos Rios has succeeded in altering the ecology of a tiny portion of the Central Valley, but the area still faces enormous water issues. According to a recent NASA study, water users in the valley are removing half of the water from the ground equivalent to the Colorado River each year by over-tapping aquifers by nearly 7 million acre-feet. Numerous areas in the valley have seen severe land subsidence as a result of this overdraft, cracking roads and sinking buildings several stories below the surface.

Managing floods is also becoming more difficult at the same time. The earth’s warming is intensifying the “atmospheric river” storms that saturate California every few years, forcing more water through the valley’s winding rivers. It was only because of a delayed spring thaw that the area avoided a disastrous disaster this year, but the hazards for the future were obvious. The formerly dry Tulare Lake resurfaced for the first time since 1997, and three people were killed when two levees in the eastern valley town of Wilton, near the Cosumnes River, ruptured. Additionally, the historically Black settlement of Allensworth flooded.

It will take several decades to correct the state’s skewed water system for the age of climate change. Up to a million acres of productive farmland will need to be retired by farmers in order to comply with California’s historic groundwater regulation law, which will go into full force by 2040 and cost billions of dollars in lost revenue. Meanwhile, billions more in funding will be needed to repair dilapidated dirt levees and channels in order to prevent flooding in the region’s cities.

Theoretically, floodplain restoration would be the best approach to address the state’s water issues because of this dual responsibility. However, the need is so great that it would take hundreds of projects to match Dos Rios in scope.

Jane Dolan, chair of the Central Valley Flood Protection Board, a state organization that oversees flood protection in the area, stated, “Dos Rios is good, but we need 50 more of it.” Do I believe that will occur during my lifetime? No, but we still need to keep pursuing it. The combined area of fifty such projects the same size as Dos Rios would be greater than 150 square miles, or the size of the city of Detroit, Michigan. That much valuable farmland would cost billions of dollars to buy, to remove the old levees, and to plant new trees.

Even while Rentner was successful in raising funds for Dos Rios, the nonprofit’s fragmented strategy was never able to support restoration projects of this magnitude. The federal and state governments are the only feasible suppliers of that amount of funding. Because Central Valley farmers have not backed floodplain restoration, neither has ever committed large public funds to it. However, things have begun to shift. Legislators in the state allocated $40 million earlier this year to finance fresh restoration initiatives. Fearing a financial crunch, Governor Gavin Newsom attempted to cut funding at the beginning of the year but was forced to backtrack following strong opposition from local politicians along the San Joaquin. The majority of this additional funding went directly to River Partners, and the company has

However, establishing the ribbon of natural floodplains that Dolan outlines will still be challenging, even if charitable organizations like River Partners manage to secure billions more dollars to purchase agricultural property. This is because the Central Valley’s river property is among the world’s most productive agricultural lands, and its owners have no need to sell in order to forfeit potential earnings.

Bowles Farm’s sixth-generation farmer, Cannon Michael, stated, “Maybe we could do it some time down the road, but we’re farming in a pretty water-secure area.” Bowles Farm is located on the upper San Joaquin River. He has the right to use water from the state’s canal system, and there are sizable aquifers beneath his land that are nourished by river seepage. “It’s a difficult calculation because we produce, we use the land for other purposes, and we employ a lot of people.”

It might not be necessary for farmers who are running out of groundwater to sell their land in order to replenish their aquifers. Growing grapes in the eastern valley along the Kings River, Don Cameron is the creator of a method that reclaims groundwater by purposefully flooding crop fields. He utilized a set of pumps to draw the flood of melting snow off the river and onto his grapes earlier this year as it came rushing along the Kings. The grapes fared quite well as the flood subsided and filled Cameron’s subterranean water bank.

Large agricultural interests are significantly more amenable to this type of recharge project since it permits farmers to maintain their properties. The California Farm Bureau has thrown its support behind recharge projects like Cameron’s because they let farmers continue farming, even though it only supports pulling agricultural land out of commission as a last resort. Other farmers have embraced the state government’s efforts to support this type of water capture: valley landowners may have captured and stored about 4 million acre-feet of water this year, according to official estimates.

“We have a more farm-centric approach, but I’m aware of Dos Rios, and I think it serves a very good purpose when it comes to providing benefits to the river,” said Cameron.

However, Joshua Viers, a watershed scientist at UC Merced, asserts that the demand for Dos Rios-like projects may be reduced by these on-farm recharge initiatives. A project like Cameron’s not only offers no ecological or flood management benefits, but it also benefits the aquifer considerably more narrowly by concentrating water in a small area of land as opposed to letting it seep over a large region.

He stated, “You’re getting recharge that otherwise wouldn’t happen if you can build this string of beads down the river, with all these restored floodplains, where you can slow the water down and let it stay in for long periods of time.”

It will be challenging to duplicate Dos Rios’ achievement as long as landowners view floodwater as a tool to assist their farms rather than as a force that must be respected. In the next decades, River Partners’ greatest obstacle will not be money but rather this deeply held belief about the natural environment. Rentner and her associates would have to turn over farmland all over the state to construct Viers’ “string of beads.”

Doing so in a northern region such as Sacramento, where flood bypasses on agricultural land were created by government a century ago, is one thing. Doing it in the Tulare Basin, further south, is a quite different story. There, the influential farm business J. G. Boswell is alleged to have diverted floodwater toward neighboring communities in an attempt to preserve its own tomato harvests. River Partners is allocating a portion of the recently allocated state funds to restoration initiatives in this region; nonetheless, these are merely minor conservation initiatives that do not transform the valley’s topography in the same way as Dos Rios.

River Partners will need to persuade hundreds of farmers that it is worthwhile to cede a portion of their land in order to protect endangered species, flood-prone cities, other farmers, and climate resilience in order to export the Dos Rios model. With perseverance and honest communication, Rentner was able to forge that consensus at Dos Rios, but the road to recovery for the rest of the state will probably be more arduous. Over the next few decades, Californian farmers will have to retire thousands of acres of productive land in response to growing costs and water constraints. In addition, when storms become more intense due to global warming and levees collapse, additional acres will be constantly at risk of flooding. When landowners lease their properties to solar firms or sell them to

Rentner stated, “It’s going to be a challenge.” “We hope that a few will reconsider and suggest that, before we complete this sale, we ought to sit down and discuss our legacy and what we’re leaving behind with the folks in the conservation community. Perhaps the highest bidder isn’t the only option.

For the Latest, Current, and Breaking News news updates and videos from thefoxdaily.com. The most recent news in the United States, around the world , in business, opinion, technology, politics, and sports, follow Thefoxdaily on X, Facebook, and Instagram.