Placental cells possess a unique ability to stimulate innate immunity and maintain it active in the absence of infection. It entails creating and distributing a phony virus.

| Topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Placenta and immune tolerance | The placenta is the organ that connects the mother and the fetus, and allows the transport of nutrients and oxygen. It also protects the fetus from the mother’s immune system, which would otherwise reject it as foreign. |

| Placenta’s molecular trick | The placenta uses a molecular trick to feign illness. It creates a fake virus from its own RNA and activates a mild immune response. This prevents the mother’s immune system from attacking the placenta or the fetus. |

| Interferon lambda | Interferon lambda is an immune signaling protein that is produced by the placenta in response to the fake virus. It helps to modulate the immune system and create a balance between protection and tolerance. |

| Implications for health | Understanding how the placenta achieves immune tolerance could lead to new treatments for conditions such as preeclampsia, a complication of pregnancy that causes high blood pressure and organ damage. It could also help to improve organ transplantation and cancer immunotherapy. |

Table of Contents

The original version of this story appeared in Quanta Magazine.

It seemed like a brilliant strategy when you were a kid: squirt yourself with hot water, stumble into the kitchen, and shriek louder than angels can. Your parents would be persuaded to believe you have a fever and send you home from school with just a touch of your hot forehead.

Despite their meticulous planning and execution, these theatrics most likely didn’t have the desired effect. However, a recent study that was published in Cell Host & Microbe indicates that a similar strategy helps developing humans and other mammals provide a more compelling picture long before birth.

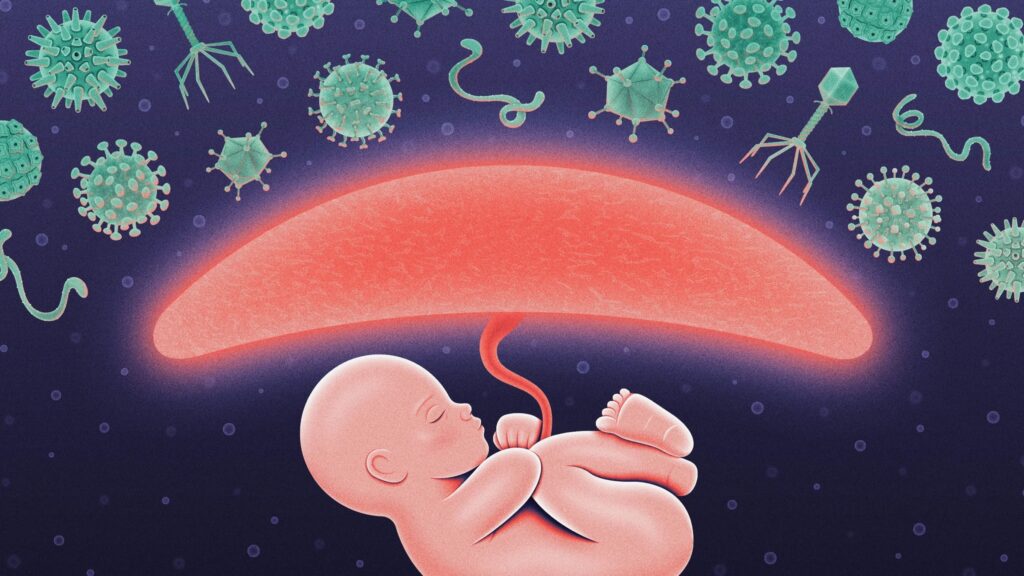

The placenta, the fetal organ that connects a child to its mother, uses a molecular trick to mimic disease, as demonstrated by the study. It keeps the immune system functioning at a moderate, steady speed to shield the contained fetus from viruses that evade the mother’s immune system by acting as though it is under viral attack.

According to the findings, certain cells could be able to trigger a mild immune response before an infection occurs, which could offer modest protection for sensitive organs.

According to Jonathan Kagan, an immunobiologist at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital who was not involved in the new work, the notion that cells could activate immune responses in advance “very much violates one of the views that immunologists have”.

Jonathan Kagan, an immunobiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School who was not involved in the current work, said that the notion of cells triggering immune responses proactively “very much violates one of the views that immunologists have.”

However, the latest research indicates that the placenta defies these regulations. It activates defenses before it needs to and then keeps them activated without endangering the fetus or itself.

Lead author of the new article and associate professor of molecular pharmacology at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Hana Totary-Jain, stated that “it protects but doesn’t damage.” “How intelligent evolution is.”

The Placenta Is Not Real Ill

It was by accident that Totary-Jain uncovered the placenta’s trickery. She described the mega-cluster of genes she and her colleagues were studying as “a monster” that was expressed in the placenta. She was shocked to see that the mega-cluster had activated the gene for the immunological signaling protein interferon lambda in addition to genes that control placental growth. Why did it still function in uninfected, healthy cells?

Years passed until Totary-Jain and her colleagues finally discovered the solution: the placental cells had created a viral clone using RNA taken from their own genomes in order to trick their immune systems.

Our genes serve as molecular historical museums of evolution. Viruses have introduced parts of their genetic material into the DNA of their hosts since the dawn of life on Earth. Interspersed within the genes that encode proteins are genetic remnants from past microbial incursions.

A DNA fragment known as an Alu repeat is among the most prevalent viral elements that continue to exist in human genomes. Alus make up at least 13% of the human genome; the Totary-Jain mega-cluster included more than 300 copies of this gene. She surmised that the placenta’s immune system was being activated by those Alu repeats. However, her coworkers advised her not to go in that direction.

“I was told to forget about Alus, don’t work with him, and don’t touch him,” stated Totary-Jain. It is difficult to analyze the potential functions of a particular group of Alus due to their abundance in the genome.

However, the evidence linking Alus was too strong to dismiss. Following years of meticulous research, Totary-Jain’s group demonstrated that transcripts of Alu repeats in the placenta generated fragments of double-stranded RNA, a molecular shape that our cells identify as being viral in origin. The cell produced interferon lambda in response to detecting the bogus virus.

According to Kagan, “the cell is essentially disguising itself as an infectious agent.” “As a result, it acts as though it is infected after convincing itself that it is.”

Diminished Immunity

Particularly when it comes to antiviral responses, immune reactions might be harmful. Since viruses are most deadly when they are already inside a cell, part of the mechanism by which most immune responses combat viral infections function is the destruction and elimination of infected cells.

Cells yell “Virus!” at their own peril because of this. Alu sequences are strongly inhibited in most tissues, preventing them from ever having the opportunity to simulate a viral onslaught. However, it appears that the placenta deliberately creates that particular situation. How does it strike a compromise between the developing embryo’s health and a possibly harmful immune response?

Totary-Jain’s team observed in mouse tests that the developing embryos appeared to be unaffected by the double-stranded RNAs and subsequent immunological response from the placenta. Rather, they shielded the embryos from infection by the Zika virus. Because the placental cells activated the kinder defenses of interferon lambda, they were able to walk the tightrope and protect the embryos without inciting a harmful immune reaction.

Type I and type II interferons are usually the first to react to double-stranded Alu RNA escapees. They rapidly attract inflammatory immune cells to the infection site, causing tissue damage and even autoimmune illness. Contrarily, type III interferons include interferon lambda. It produces a weaker immune response that can be long-lasting in the placenta by acting locally and exclusively interacting with cells within the tissue.

It is still unclear how placental cells are able to selectively activate interferon lambda, which keeps the immune response at a simmer rather than a boil. However, Totary-Jain believes she knows why placental cells developed this ruse that other cells appear to avoid: Perhaps the placenta can afford to take immunological risks that other tissues cannot because it is removed at birth.

The results show that the placenta possesses a new defense mechanism for the fetus in addition to the mother’s immune system. For the purpose of protecting the developing baby, the placenta has had to fortify itself against external threats because the mother’s immune system is suppressed during pregnancy.

But this trick—a fictitious virus evoking a low-level immune response—might not be specific to the placenta. A comparable phenomena in neurons was recently observed by Columbia University researchers. They saw that RNAs originating from various genomic elements formed double strands and combined to trigger an immunological reaction. Although the immune system produced less of the more lethal type I interferon in this case, it was still present. The scientists hypothesised that long-term, mild inflammation in the brain could regulate infections and avert severe inflammation and neuronal death.

Therefore, it’s plausible that immunological manipulation of this kind occurs more frequently than previously believed. Scientists can gain a better understanding of the rules by examining how the immune system appears to violate them.

This article was originally published in Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent journal of the Simons Foundation. Its goal is to improve public understanding of science by reporting on trends and developments in mathematics, the physical and biological sciences, and research advances in these fields. Reprinted with permission.

For the Latest, Current, and Breaking News news updates and videos from thefoxdaily.com. The most recent news in the United States, around the world , in business ,opinion technology, politics, and sports , follow Thefoxdaily on X , Facebook , and Instagram.