In Short

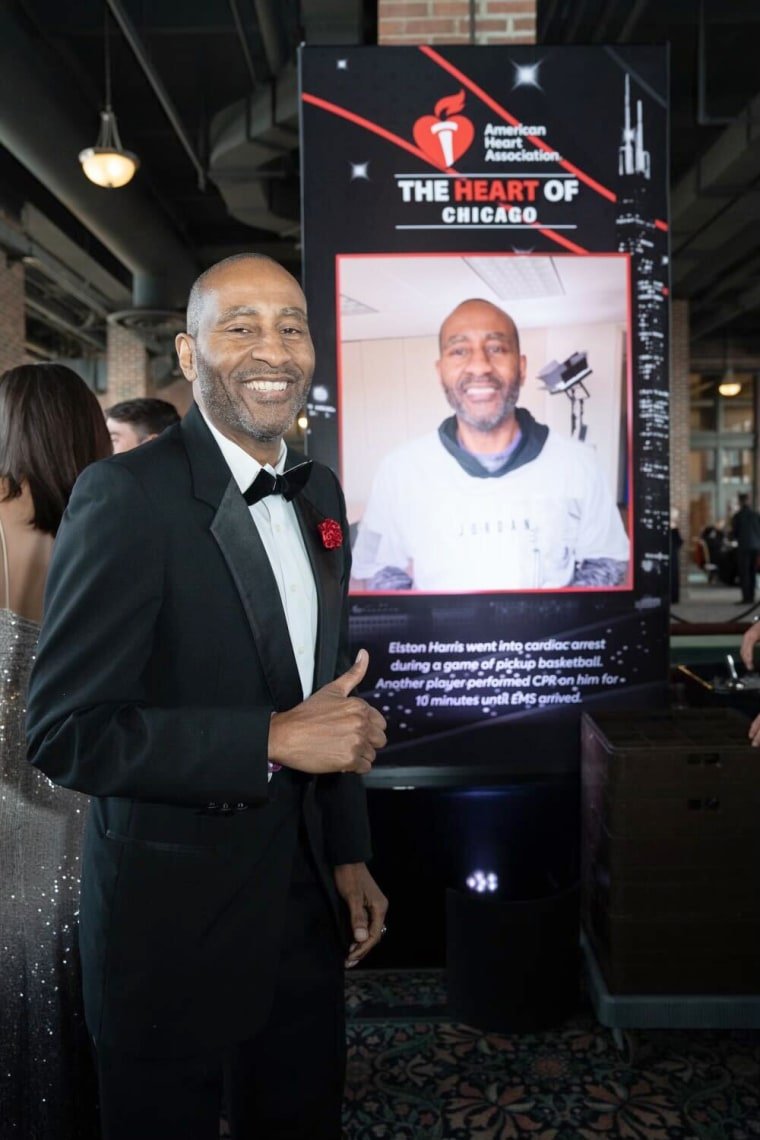

- Elston harris, a heart attack survivor, emphasizes the importance of diversity in healthcare, particularly in cardiology.

- Despite disparities, initiatives to increase the number of black physicians are gaining traction.

TFD – Delve into the story of Elston Harris, whose journey after a heart attack underscores the vital role of Black cardiologists in providing tailored care.

Elston Harris believes that heart attacks are a genetic curse.

Heart attacks claimed the lives of several males on Harris’ father’s side of the family, including his uncles. The 59-year-old Harris, a former college basketball player, came dangerously close to the same outcome following his own heart attack in 2017. The only signs he was having a heart attack that he noticed were “small” symptoms of back pain and trapped gas.

Perhaps fortunately for Harris, the curse had a silver lining: while receiving care at Advocate Trinity Hospital, a southeast Chicago medical facility, he was referred to cardiologist Dr. Marlon Everett, who provided him with a “game plan” to adhere to. This involved prioritizing God, maintaining a good diet, and focusing on his examinations. But aside from Everett’s expertise, Harris said he felt comfortable because Everett looked like him.

Harris, a Chicago resident, stated, “When you are African American or Black, you are more comfortable interacting with someone who knows, ‘OK, he might have grew up here, or he might eat this, or I heard them do that.” “So, you feel much more at ease around people who follow in your footsteps.”

According to the American Heart Association, heart disease affects about 60% of adult Black Americans, and Black Americans have higher heart disease death rates than people of other racial and cultural backgrounds.

It is uncommon, though, for Harris to have a cardiologist who looks like him. According to an Association of American Medical Colleges report from 2021, the percentage of Black cardiologists is a mere 4.2%. Similar results from a previous study that was published in the journal JAMA Cardiology in 2019 showed that Black doctors made up just 3% of cardiologists. According to the same study, 19% of cardiologists were Asian and 51% were White.

Better heart health for Black patients may result from an increase in the number of Black cardiologists.

According to an AHA statement provided to NBC News, “Underrepresented medical professionals are more likely to practice in their communities where cultural sensitivity can create trust and their presence has been shown to improve outcomes.” “When it comes to heart health, this connection is especially important among Black Americans.”

Why is the number of Black cardiologists so low?

Greensboro, North Carolina-based cardiologist Dr. Mary Branch stated that she originally developed an interest in cardiology about 20 years ago while working as an assistant to a white interventional cardiologist who was “very accepting of me.” According to her, the path to cardiology is challenging and entails four years of medical school, three years of internal medicine residency, three years of cardiology fellowship, and many board tests.

As a fourth-generation doctor, Branch said that she faced discrimination and financial hardship along the way, which she claimed is one of the reasons there aren’t as many Black doctors in the field of cardiology. These challenges are unfortunately prevalent for Black medical students.

At Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Branch was the first Black woman accepted into the cardiovascular disease fellowship. She claimed that while searching for safe accommodation, she briefly resided in a hotel during her fellowship.

Branch claimed that she was “still showing up” at her fellowship despite not having a place to stay. She said, “In all honesty, it was just God telling me you’re needed.” Thus, we must continue. But that required making many difficult decisions.

According to Branch, a lot of Black medical students may encounter severe microaggressions that may keep them from pursuing careers as cardiologists.

For Black trainees, the margin of error might be “very small,” according to her. While most medical students and residents of all races perceived high levels of mistreatment, Black people perceived more stress in medical school than white people, according to a 2006 study in the Journal of the National Medical Association. Their minority status and encounters with racial prejudice during training were the sources of their perceived stress.

According to a 2021 study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, there has only been a 4 percentage point rise in the number of Black doctors in the United States during the previous 120 years. The survey also discovered that since 1940, the proportion of Black male doctors has not changed. According to a 2021 perspective published in The Lancet, Black women make up just 2.8% of all physicians, despite the fact that there is limited information on their rates in cardiology.

Everett said that there are insufficient training programs for medical professionals who wish to specialize in cardiology. Everett is a member of the Association of Black Cardiologists, a national organization that raises awareness of the detrimental effects of heart disease on Black people. Although there may only be three or four cardiology training positions available in most schools, he claimed that “we’re just not getting those training positions.”

“We won’t have much inclusivity until there are programs requiring diversity in training programs, especially in the highly sought-after training programs like cardiology,” Everett continued.

Additionally, the organization helps to fill clinical studies with a dearth of Black volunteers by finding Black patients. According to a 2021 study that was published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health’s cardiovascular studies did not include enough Black adults.

This could imply that medical professionals lack access to the most up-to-date knowledge on how to care for Black patients.

According to Everett, “it’s critical that there be a large number of Black patients participating in trials in order for us to obtain better data—and more data implies better information, and hopefully better outcomes.”

‘A feeling of security’

The medical system’s history of racism and maltreatment of Black patients makes it difficult for many Black patients to feel comfortable and trusted when they see a Black cardiologist.

When physicians found Branch had a heart murmur following a sleep study, Nikita Oxner visited her for the first time last year. The 45-year-old Oxner claimed that she had never seen a cardiologist before and that it was “scary” to even be referred to one. But when she met Branch, those worries diminished.

Oxner was treated by Branch and found to have a disease that interferes with the heart’s ability to pump blood.

Heart issues are inherited by Oxner’s family. Her grandmother passed away from heart illness at the age of 77 in 2019 and her brother passed away unexpectedly at the age of 31 due to hypertension. She stated that her father “had hypertension, high blood pressure a majority of his life” until he passed away at the age of 39 from cancer.

According to Oxner, “she instantly understood” when she told Branch about her brother and other family members. Oxner trusted her doctor’s judgment even though she “didn’t feel good” about undergoing surgery to implant a defibrillator in her heart.

According to Oxner, who resides near Greensboro, North Carolina, “she had a lot of compassion.” “She truly helped me understand how this could change my life. She was very understanding, down to earth, and relatable.”

The fact that Branch was also a Black woman “mattered to me,” according to Oxner, a Black woman who frequently had to speak up for her health.

According to Branch, patients are more likely to adhere to healthy lifestyle modifications and heart medication regimens when they feel the extra layer of confidence and comfort that is frequently present between a Black patient and Black clinician.

For instance, she stated that “hypertension is a big thing in our community.” She stated that a Black cardiologist might also be on medicine for hypertension, “so, they can relate and connect in that way.”

Kia Smith, 42, is a Black lady who also sought cardiac care from a Black physician, similar to Oxner. Smith, a resident of Ellenwood, Georgia, stated that she saw Atlanta Heart Associates cardiologist Dr. Camille Nelson in 2020 as a result of having an increased heart rate. Smith stated that she thinks her concerns may have been written off and she might have been treated like “a dramatic walk-in” if she had gone with a non-Black cardiologist.

Smith said of Nelson, “At every turn, when I was concerned, she did not dismiss my concerns or my personal experiences.” “She also explained the science of everything to me, and we were able to get to a place where I was confident that I was going to be OK.” Nelson speculated that Smith’s symptoms might have been brought on by stress and suggested exercise regimens to improve the health of her heart.

Many Black women tell Dr. Zainab Mahmoud, a cardiologist and medical lecturer at Washington University in St. Louis, that they feel heard and understood while in her care. According to her, “having a provider who can relate to the experiences of Black patients creates this kind of trust and improves a patient-provider relationship.”

“There’s a greater chance that they’ll invite their friends and family to visit me as well,” Mahmoud continued. “I can’t even count how many times I’ve seen that happen.”

Recruiting more Black physicians to work in cardiology

Major health organizations have made it their mission to increase the number of Black cardiologists in recent years.

More than 70% of Black medical professionals receive their degrees from historically Black schools and universities, where the AHA’s Scholars program offers cardiology resources to Black students.

The group is also concentrating on more extensive initiatives: According to a statement, a good education can support the development of the next generation of Black physicians, nurses, and researchers. Increasing the proportion of Black students enrolled in graduate scientific, research, and public health programs is one of the main objectives.

The American College of Cardiology, like the American Heart Association, has made diversity initiatives to increase the number of Black, Latino, and other underrepresented group cardiologists through its internal medicine program.

The chief diversity, equality, and inclusion officer of the ACC, Dr. Melvin Echols, stated, “The problem is, it’s not just cardiology.” It’s everything related to healthcare. There are noticeably few African American physicians. Basically, I think our goal is to make it simpler for folks to actually obtain tools and knowledge.

When his life was in danger, Harris, who had survived his 2017 heart attack, said it was “by God’s grace” that he found himself at Advocate Trinity Hospital with a cardiologist he could rely on.

Regarding his cardiologist Everett, Harris remarked, “He was there during my episode and we immediately formed a relationship after that.” He has been caring for Harris “ever since.”

Conclusion

Elston Harris’s experience highlights the critical need for diversity in healthcare, particularly in cardiology, where tailored care can significantly impact outcomes. As efforts to increase Black representation in medicine continue, the importance of culturally competent care remains paramount.

Connect with us for the Latest, Current, and Breaking News news updates and videos from thefoxdaily.com. The most recent news in the United States, around the world , in business, opinion, technology, politics, and sports, follow Thefoxdaily on X, Facebook, and Instagram .