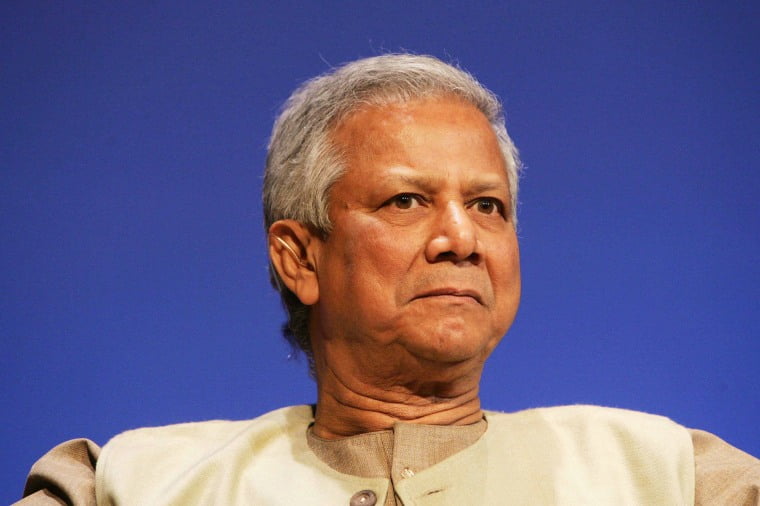

Muhammad Yunus, who pioneered the use of microcredit to reduce poverty and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, told NBC News that the accusations are politically driven.

In Short

TFD –Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus is on the brink of jail in Bangladesh amidst politically motivated accusations, raising questions of justice.

A Nobel Peace winner who is referred to as the “banker to the poor” may go to jail in Bangladesh, where he was born, since he is facing numerous legal allegations that he claims are politically motivated.

Along with three other executives from his telecommunications firm, Muhammad Yunus, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his innovative use of microcredit to reduce poverty, was found guilty in January of breaking labor regulations in Bangladesh and was given a six-month prison sentence.

Their bail might be revoked during an appeal hearing on Sunday, and if Yunus is found guilty of over 200 additional charges—including money laundering, tax evasion, and corruption—he could face much longer sentences.

Along with his global followers, Yunus, 83, has denied all charges and claims that Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government is harassing him through the legal system.

In a Zoom interview with NBC News on Thursday from Dhaka, the capital of South Asia, Yunus stated, “She hates me to the core.” “I am not sure why it transpired in that manner.”

The case against Yunus was “tried with unusual speed,” according to the State Department, which has sanctioned Bangladeshi nationals accused of tampering with the Jan. 7 election that saw Hasina win a fourth consecutive term. This could be an attempt to “harass and intimidate” Yunus.

Spokesman Matthew Miller told reporters on February 13 that “we are concerned that the alleged abuse of labor and anti-corruption laws could raise questions about the rule of law and dissuade future foreign direct investment, and we encourage the Bangladeshi government to ensure a fair and transparent legal process for Dr. Yunus as the appeals process continues.”

In September, a Bangladeshi deputy attorney general was dismissed for informing media that Yunus was the target of legal harassment.

People from throughout the world have expressed their support for Yunus. Nearly 200 well-known people from around the world, including 108 Nobel laureates, wrote an open letter to Hasina in August requesting that a panel of judges with no bias evaluate the accusations against Yunus.

The letter stated, “We are confident that any thorough review of the labor law and anti-corruption cases against him will result in his acquittal.”

Former Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and former President Barack Obama signed it. In 2009, Obama presented Yunus with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award.

Twelve U.S. senators also called for an end to Yunus’s “persistent harassment” and “the pattern of abusing laws and the justice system to target critics of the government more broadly” in a letter to Hasina in January.

Bangladeshi officials claim that their nation has an independent legal system and that outside critics are unjustly meddling.

In response to the Nobel laureates’ letter in September, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated, “The signatories to the letter would be well advised to counsel Dr. Muhammad Yunus to operate within the bounds of law in lieu of making unjustified insinuations about Bangladesh’s democratic and electoral processes.”

Bangladesh, a parliamentary democracy with 170 million citizens and a majority of Muslims, is the seventh most populous and one of the least developed countries in the world. Its score has been continuously declining since it was ranked 127th out of 142 countries in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index last year.

“It is imperative that we examine Dr. Muhammad Yunus’s situation within the larger framework of how the judiciary is being used as a weapon against the opposition,” stated Mubashar Hasan, an adjunct fellow at Western Sydney University in Australia and a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oslo in Norway.

The opposition boycotted and the State Department criticized the January election, which was won by Hasina, 76, and her Awami League, as being neither free nor fair. Voter turnout in Bangladesh was under 40%, according to election officials, although it was over 80% in the previous election in 2018.

Tens of thousands of opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party officials and members were detained in the months preceding the election, while anti-government protests claimed the lives of at least two persons.

Hasina has downplayed the boycott by the opposition and claimed that the election was impartial.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Bangladesh has been contacted by NBC News on Yunus’ legal charges and the allegations of electoral meddling.

“This is my hometown.”

After Bangladesh got independence in 1971, Yunus, who had been a professor at Middle Tennessee State University, went back to his native country. He established Grameen Bank in 1983 with the goal of enabling low-income people, particularly women, to launch their own enterprises through small, long-term loans on flexible terms—a practice known as microcredit.

Though the effects have been uneven, the idea behind these loans—which are now widely available globally, including in the US—was to help end poverty.

Hasina has been attacking Yunus nonstop since taking back office in 2009. She has called him a “bloodsucker” of the underprivileged and said that Grameen Bank is charging them outrageous interest rates.

Yunus refuted claims that his company had participated in abusive tactics, asserting that there was a distinction between “right microcredit” and “wrong microcredit,” wherein lenders impose exorbitant interest rates.

“Microcredit ought to be conducted as a social enterprise, rather than a profit-driven venture,” he declared.

Hasan suggested that Hasina would view Yunus as a possible opponent as well. Yunus had declared in 2007 that he intended to form a political party to combat corruption, but he later withdrew the notion. Yunus declared on Thursday that he “had no desire to work in politics.”

Yunus stated that Hasina “sees that I’m very popular among the people because I’ve worked for them and I’ve visited almost every village in the country doing my work,” which is the only reason she could understand him as a political danger.

Hasan, the author of two books on Bangladeshi politics, stated that Hasina’s government “may go harder” against Yunus following her reelection in January. According to Yunus, several of his firms were forcibly taken over by “outsiders” for several days last month, and the police turned a blind eye.

Hasan stated, “They have at least four more years to indisputably rule the nation.” “Dr. Muhammad Yunus, the opposition, human rights advocates, and democracy advocates are not going to be pleased with this news.”

Despite friends in the US and other countries pushing him to leave Bangladesh, Yunus says he cannot because this is “where I grew up.”

He expressed concern about his colleagues as well.

“What happens to them if I leave? They’re going to jail,” he declared. “And I’ll put the blame on myself, asking why I let them go to jail while I was having fun in another nation.”

Conclusion

Muhammad Yunus’s potential imprisonment underscores the dangers of political persecution and highlights the need for fair and transparent legal processes.

Connect with us for the Latest, Current, and Breaking News news updates and videos from thefoxdaily.com. The most recent news in the United States, around the world , in business, opinion, technology, politics, and sports, follow Thefoxdaily on X, Facebook, and Instagram .