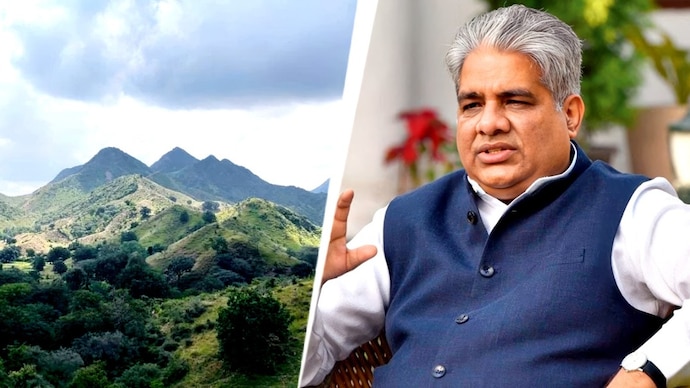

The long-simmering controversy over the protection of the Aravalli mountain range has once again taken centre stage in national politics after Union Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav accused the previous congress-led Rajasthan government of allowing rampant illegal mining. Speaking to India Today TV, Yadav asserted that most of the images circulating on social media, which critics claim show recent environmental damage, actually depict mining operations that were sanctioned and carried out years ago.

“Every image that influencers post online shows mines that were operational during the Congress era. These mines were abandoned after eight to ten years of extraction,” Yadav said, pushing back against allegations that the Centre’s recent policy changes are responsible for ecological degradation in the Aravallis.

The controversy has its roots in the Centre’s move to adopt a uniform definition of the Aravalli Hills, following repeated directions from the Supreme Court. The court had observed that the absence of a consistent definition across states led to regulatory loopholes, arbitrary grant of mining leases, and unchecked exploitation of one of India’s oldest mountain systems.

According to Yadav, the new definition includes all landforms—regardless of height—within the intervening area between hills, covering slopes, valleys, and associated geological features. A cluster of two or more hills, each at least 100 metres high and located within 500 metres of one another, will qualify as part of the Aravalli range under this framework.

The minister underlined that this step was not taken lightly. “Because of rampant illegal mining in Rajasthan, such a definition became absolutely necessary,” he said, adding that Rajasthan alone accounts for the bulk of mining activity within the Aravalli region, which spans four states—Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, and Delhi.

Citing official data, Yadav claimed that out of 1,008 mines operating in Rajasthan, nearly 700 were established during the tenure of former Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot. He argued that these decisions weakened the ecological integrity of the Aravallis and forced judicial intervention.

The Supreme Court, Yadav noted, stayed several mining leases after finding that they had been allotted in a “non-transparent and arbitrary manner,” warning that such practices could permanently destroy the essential characteristics of the Aravalli ecosystem. The court also emphasised that environmental protection could not vary from state to state.

| Key Issue | Government Position | Opposition / Activist View |

|---|---|---|

| Cause of Environmental Damage | Illegal mining during Congress-era governance in Rajasthan | Fear that new definition weakens protection |

| Mining Area Permitted | Only 0.19% of the total Aravalli landscape | Even small areas can disrupt fragile ecosystems |

| Legal Basis | Supreme Court-mandated uniform definition | 100-metre height criterion is arbitrary |

| Eco-sensitive Zones | Mining banned within 1 km of protected areas | Ground-level enforcement remains weak |

Yadav further clarified that mining is completely prohibited within one kilometre of eco-sensitive zones, including areas surrounding four tiger reserves and over twenty wildlife sanctuaries. Large sections of the Aravalli range in Delhi, Gurgaon, Faridabad, and parts of southern Rajasthan are already designated as no-mining zones.

Addressing concerns that economic extraction is being prioritised over ecology, the minister argued that the Aravallis have supported human civilisation for centuries. “There are historic forts, rivers, settlements, and livelihoods that have coexisted with this landscape,” he said, stressing that development and conservation must go hand in hand.

“Even where extraction is permitted, it is extremely limited. Overall mining accounts for just 0.19 per cent of the Aravalli area. In the most intensive zones, it does not exceed 0.1 per cent,” Yadav explained, adding that materials like marble are extracted primarily for domestic needs.

Environmental groups and opposition leaders, however, remain sceptical. Several activists argue that the new definition may exclude smaller hillocks and recharge zones that play a crucial role in groundwater replenishment, biodiversity conservation, and climate resilience in northwestern India.

Protests have been reported from parts of Rajasthan, including Udaipur, where demonstrators have demanded that the entire Aravalli range be declared a total no-go zone for mining. They warn that even limited extraction could accelerate desertification, worsen air pollution, and reduce water availability in already-stressed regions.

Former Rajasthan Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot has rejected the Centre’s claims, accusing it of shifting blame and diluting environmental safeguards. He has maintained that the Congress government acted within the law and that the Centre’s narrative is politically motivated.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has admitted petitions challenging the 100-metre height benchmark used in the definition, with petitioners cautioning that such criteria may have “grave ecological consequences” if not revisited.

As legal scrutiny continues and political tempers rise, the Aravalli debate highlights a deeper national dilemma—how to balance economic requirements, federal coordination, and environmental preservation. With climate change intensifying and water scarcity becoming more severe, the future of the Aravalli Hills remains a test case for India’s environmental governance.

For breaking news and live news updates, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Read more on Latest India on thefoxdaily.com.

COMMENTS 0