Pakistan’s capitulation in Dhaka on December 16, 1971, was not merely a military loss. According to its own post-war investigation, it was the final collapse of a regime weakened by corruption, moral decay, alcohol, and sexual excess. The battlefield defeat, the inquiry suggested, was only the visible outcome of a far deeper rot within the state and its military leadership.

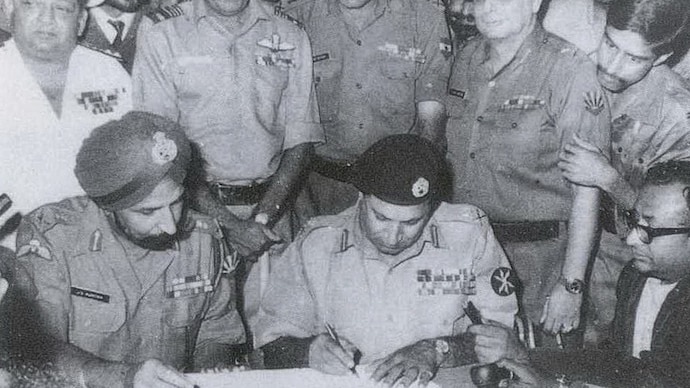

At the surrender ceremony, Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi sat hunched over the table, pen in hand, signing away East Pakistan. Across from him was the victorious Indian Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, flanked by commanders of the Bangladeshi Mukti Bahini. Behind Niazi stood more than 90,000 Pakistani soldiers—soon to become prisoners of war in the largest military surrender since World War II.

Beyond the barricades, angry crowds in newly independent Bangladesh pressed forward, furious at decades of oppression by West Pakistan. Indian tricolours fluttered overhead, while Pakistan’s military pride lay crushed in the dust of Dhaka.

Far away in Rawalpindi, Pakistan’s military dictator and Commander-in-Chief, General Yahya Khan, was reportedly nursing a hangover as his eastern command collapsed. Hours before the surrender, the woman widely known as “General Rani” had left his residence. Witnesses would later describe the previous night’s gathering as particularly raucous.

By the end of the war, 93,000 soldiers were captured, and Pakistan was effectively split in two. In the aftermath, the nation confronted a disturbing question that would haunt it for decades: how did it all go so wrong?

The Pakistani government’s own inquiry would conclude that the answer was more humiliating than the defeat itself.

The Reckoning: The Hamoodur Rahman Commission

In the stunned aftermath of the war, Pakistan’s new leader, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, appointed Chief Justice Hamoodur Rahman to head an investigating commission. Its mandate was explicit: determine why East Pakistan was lost, identify those responsible, and recommend action.

What the commission uncovered was so disturbing that even hardened military officers reportedly recoiled from its findings.

After months of testimony and analysis, the Hamoodur Rahman Commission (HRC) submitted its main report in 1974. But it was the supplementary report—particularly the chapter titled “Moral Aspects”—that shook Pakistan. The conclusion was stark: Pakistan did not lose solely because of poor strategy or battlefield mistakes. It lost because its senior military leadership had succumbed to corruption, debauchery, and moral collapse.

The commission stated that many senior officers had “indulged in large-scale corruption” and adopted “highly immoral and licentious ways of life,” severely impairing their leadership and professional competence.

In plain terms, the inquiry suggested that Pakistan’s generals were too distracted by alcohol and women to fight a war.

The Drunk at the Helm: Yahya Khan

General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan seized power in a 1969 coup, presenting himself as the strongman Pakistan needed. Charismatic and known for his heavy drinking, Yahya promised stability and a return to democracy. Instead, his rule became synonymous with excess and chaos.

By 1971, Yahya’s Rawalpindi residence had acquired an unsavoury reputation. This was the same period when East Pakistan descended into civil war following Operation Searchlight and the refusal to honour Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s electoral victory.

While the commission stopped short of naming every individual involved, it was clear that Yahya and his inner circle had fostered a culture of intoxication and personal indulgence at the highest levels of power.

Even as desperate messages arrived from Dhaka reporting catastrophic losses, witnesses described nights of heavy drinking at the top. Officers seeking urgent instructions were told the Commander-in-Chief was “indisposed”—a euphemism that fooled no one.

The commission concluded that this moral vacuum at the top inevitably flowed downward. If the head of state treated command as secondary to cocktails, discipline throughout the ranks was bound to erode.

The Power Behind the Throne: General Rani

Akleem Akhtar, better known in Pakistani political folklore as “General Rani,” became a powerful symbol of the regime’s corruption.

Described as beautiful, ambitious, and ruthless, Akleem reportedly became Yahya Khan’s closest confidante. Though she held no official position, her influence was widely acknowledged. Those seeking favours—politicians, businessmen, and military officers alike—knew that access to power ran through her.

Operating from Yahya’s residence, she became a gatekeeper and fixer, blending state policy with personal relationships. Her prominence came to symbolise everything wrong with the regime: unaccountable power, personal access, and institutional decay.

Though not explicitly named in the most damning sections of the HRC report, her role became embedded in Pakistan’s national memory of 1971 as an emblem of how personal relationships corroded the chain of command.

The Songstress at War: Noor Jehan

While General Rani symbolised corruption, legendary singer Noor Jehan came to represent the frivolity of power.

A cultural icon on both sides of the border before Partition, Noor Jehan became Pakistan’s most celebrated voice after 1947. Her patriotic songs were broadcast during the 1971 war, urging soldiers to fight on.

Yet post-war accounts alleged that during the most critical months of the conflict, Noor Jehan spent evenings at Yahya Khan’s Lahore residence. The image seared into public consciousness was devastating: while the nation burned, its leader entertained the country’s most famous singer.

Though not formally indicted by the commission, Noor Jehan became part of the wider narrative of distraction and decadence at the top of the state.

Niazi: The Inadequate Commander

If Yahya embodied moral collapse at the top, Lieutenant General Niazi represented its consequences on the ground.

As commander of Pakistan’s Eastern Command, Niazi presided over the forces in East Pakistan. The commission found him guilty of “conduct unbecoming an officer,” citing sexual misconduct, corruption, and a complete breakdown of discipline.

Testimony revealed that his behaviour eroded authority so thoroughly that troops openly questioned why they should behave honourably when their commander did not.

When the Indian offensive began in December 1971, Niazi commanded an army that neither trusted nor respected him. The surrender followed swiftly.

The Thesis of Moral Collapse

The Hamoodur Rahman Commission ultimately argued that Pakistan’s defeat stemmed not primarily from military miscalculations, but from moral bankruptcy.

An army consumed by “wine, women, and corruption,” it concluded, could not defend a nation.

A Convenient Diversion

At the same time, the focus on personal vice allowed Pakistan to avoid confronting deeper truths: political repression in East Pakistan, the brutality of Operation Searchlight, and the refusal to accept democratic outcomes.

Blaming individual immorality was easier than confronting systemic failure.

The Aftermath and an Unfinished Reckoning

Yahya Khan resigned days after the defeat and lived out his life in obscurity. Niazi was retired, disgraced, and later claimed he was made a scapegoat. Neither faced a full public trial.

The commission’s recommendations were largely buried, its full report suppressed for decades.

The irony was complete: a commission meant to deliver accountability was itself silenced.

Yahya Khan was intoxicated when his country fell apart. Pakistan, decades later, still suffers from the hangover.

For breaking news and live news updates, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Read more on Latest India on thefoxdaily.com.

COMMENTS 0