- Introduction: A Relationship Built on Strategic Convenience

- The Geostrategic Value of Pakistan After 1947

- The Formation of Cold War Alliances

- Badaber and the U-2 Crisis

- The Afghan Jihad and Operation Cyclone

- Rivalry with India and Strategic Miscalculations

- The War on Terror

- The Abbottabad Raid and Diplomatic Strain

- The 2021 US Withdrawal from Afghanistan

- The Strategic Contrast with India

- Conclusion: A Cycle That Repeats

Introduction: A Relationship Built on Strategic Convenience

For more than seven decades, the relationship between the United States and Pakistan has oscillated between strategic embrace and calculated distance. It remains one of the most complex alliances in modern geopolitical history — shaped by Cold War compulsions, regional rivalries, and shifting global priorities. Time and again, Islamabad positioned itself as a frontline ally of Washington, only to find itself sidelined once American objectives were achieved.

Pakistan’s Defence Minister Khawaja Asif once described the relationship in Parliament as deeply transactional, stating that the United States had treated Pakistan “worse than toilet paper.” While the remark was politically sharp, it reflected a broader national sentiment — that Pakistan has often served as a strategic instrument rather than an equal partner.

However, any serious geopolitical analysis must go beyond rhetoric. The historical record reveals a recurring cycle of dependency, strategic calculation, and domestic policy decisions that contributed to this pattern. Understanding this trajectory requires examining both American strategic priorities and Pakistan’s own choices.

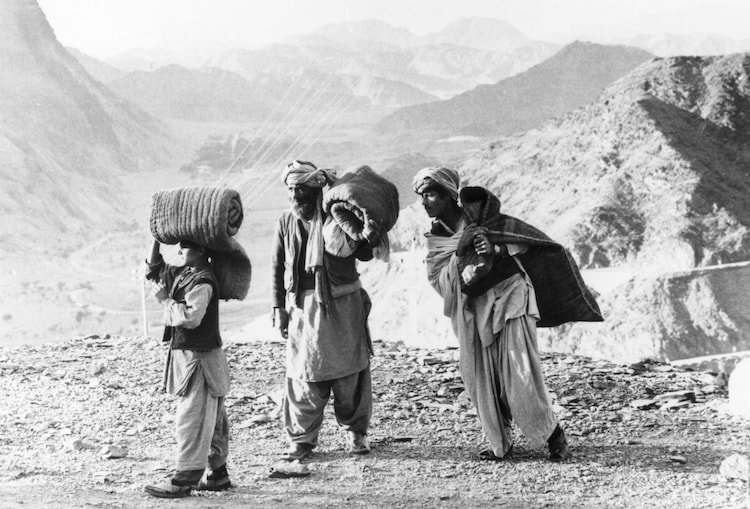

The Geostrategic Value of Pakistan After 1947

When Pakistan emerged in 1947 following the partition of British India, it faced immediate security challenges, particularly in relation to India and Kashmir. Initially, Washington appeared more inclined toward India under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, whose democratic credentials and global stature carried weight.

Yet India’s policy of non-alignment during the early Cold War disappointed American planners seeking committed allies against Soviet expansion. This opened space for Pakistan to present itself as a willing partner.

In 1949, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin extended an invitation to Pakistan — a move widely seen as diplomatic maneuvering. Soon afterward, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan accepted an invitation to Washington instead, marking Pakistan’s decisive tilt toward the United States. During his 1950 visit, Khan emphasized Pakistan’s strategic geography — positioned between South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East — portraying the country as a bulwark against communism.

For Pakistan, the motivation was clear: economic and military support to counterbalance India. For Washington, Pakistan offered geographic access and alignment within the containment strategy.

The Formation of Cold War Alliances

The partnership deepened in the 1950s through Pakistan’s entry into two major US-backed military alliances:

- Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), established in 1954 to curb communist influence in Asia.

- Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), formed in 1955 to limit Soviet expansion in the Middle East.

These alliances created optimism in Islamabad. Pakistani leadership believed alignment with Washington would strengthen its position against India, especially over Kashmir. However, US strategic doctrine made clear that these alliances were designed for Soviet containment, not South Asian disputes.

The structural imbalance was evident early: Pakistan sought security guarantees; the United States sought strategic positioning.

Badaber and the U-2 Crisis

In the late 1950s, the CIA established a covert intelligence facility at Badaber near Peshawar. Officially termed a communications center, it functioned as a sophisticated electronic listening station and launch site for U-2 reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory.

On May 1, 1960, pilot Francis Gary Powers took off from this base on a surveillance mission across the Soviet Union. His aircraft was shot down, and he was captured alive. The incident triggered a major international diplomatic crisis.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly condemned the operation and reportedly warned that Peshawar could become a target if such missions continued. The episode illustrated the risks inherent in transactional alliances: Washington gained intelligence; Pakistan gained military aid — but also assumed strategic exposure.

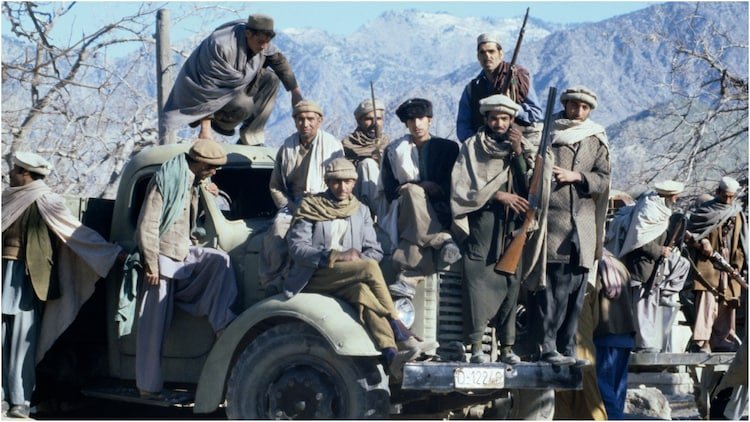

The Afghan Jihad and Operation Cyclone

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 dramatically enhanced Pakistan’s strategic importance. Under US President Jimmy Carter, and later Ronald Reagan, Washington sought to counter Soviet expansion by supporting Afghan resistance fighters.

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s military ruler, aligned fully with American objectives. Through Operation Cyclone, the CIA channelled billions of dollars in arms and funding to Afghan mujahideen via Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

The short-term objective of weakening Soviet influence was achieved. However, the long-term costs were significant. Pakistan absorbed between three and five million Afghan refugees. Weapons proliferation surged. Narcotics networks expanded. Radical madrassa infrastructure grew along the Afghan border.

Once Soviet forces withdrew, US engagement declined rapidly. In 1990, the Pressler Amendment imposed sanctions on Pakistan over its nuclear program — a program that had been strategically overlooked during the 1980s partnership.

Rivalry with India and Strategic Miscalculations

Pakistan’s alignment with Washington was consistently shaped by rivalry with India. Leaders in Islamabad believed American military backing would provide leverage in regional conflicts.

During the 1965 Indo-Pak war, Pakistan assumed its US-supplied arsenal offered decisive advantage. Instead, Washington imposed an arms embargo on both countries, disproportionately affecting Pakistan due to its reliance on American equipment.

The 1971 war proved even more consequential. Despite symbolic movements of the US Seventh Fleet into the Bay of Bengal, the outcome was unchanged. The war resulted in the creation of Bangladesh, fundamentally reshaping South Asia.

The expectation of guaranteed American intervention repeatedly proved unrealistic.

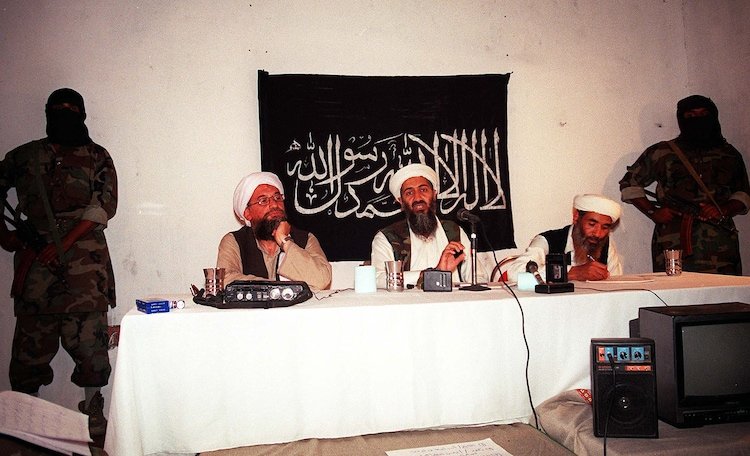

The War on Terror

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Pakistan once again became indispensable. Under General Pervez Musharraf, Islamabad joined the US-led War on Terror.

Pakistan facilitated NATO supply routes into Afghanistan, provided intelligence cooperation, and conducted military operations in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).

However, the internal repercussions were severe. The emergence of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) marked violent blowback. In 2014, the TTP carried out the Army Public School attack in Peshawar, killing 149 people, including 132 children.

Militancy cultivated in earlier conflicts turned inward, destabilizing Pakistan itself.

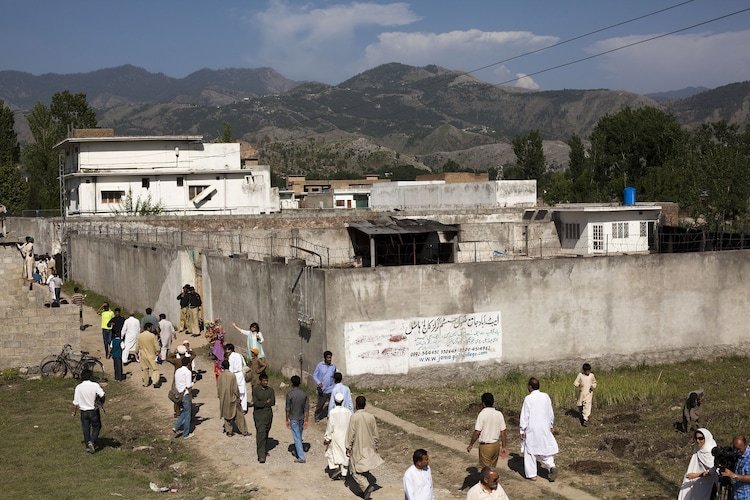

The Abbottabad Raid and Diplomatic Strain

On May 2, 2011, US Special Forces conducted a unilateral raid in Abbottabad that killed Osama bin Laden. The operation was carried out without prior notification to Islamabad, severely damaging trust.

Pakistan’s Parliament condemned the violation of sovereignty, and public opinion shifted sharply against close cooperation with Washington. The incident symbolized the depth of mistrust embedded in the alliance.

The 2021 US Withdrawal from Afghanistan

In April 2021, President Joe Biden announced the complete withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. By August, the Taliban had regained control.

Pakistan once again faced instability along its western border, renewed refugee pressures, and the resurgence of militant threats. Pakistani officials expressed frustration that Islamabad was left managing the consequences of yet another shifting American strategic priority.

The Strategic Contrast with India

While Pakistan pursued alliance-driven security, India adopted a strategy of calibrated autonomy. Over time, US–India ties strengthened through economic integration, technological cooperation, and the 2005 Civil Nuclear Agreement.

India avoided formal alignment during the Cold War, invested in institutional development, and diversified its partnerships. Today, US–India relations are defined by long-term strategic convergence rather than dependency.

This contrast remains central to debates within Pakistan’s strategic community.

Conclusion: A Cycle That Repeats

A careful examination of US–Pakistan relations reveals a recurring pattern: Washington identifies a strategic objective; Pakistan becomes a frontline ally; assistance flows; objectives shift; engagement recedes.

The consequences for Pakistan have included internal instability, economic volatility, demographic pressures, and strained diplomacy. However, external decisions alone do not explain this trajectory. Domestic policy choices, civil–military dynamics, and regional strategies played decisive roles.

The enduring question is not whether the United States will reprioritize — global powers inevitably do. The deeper question is whether Pakistan will redefine its foreign policy to prioritize institutional strength, economic resilience, and strategic autonomy.

In geopolitics, nations that rely solely on external utility risk becoming disposable. Those that invest in self-reliance endure.

For breaking news and live news updates, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Read more on Latest World on thefoxdaily.com.

COMMENTS 0